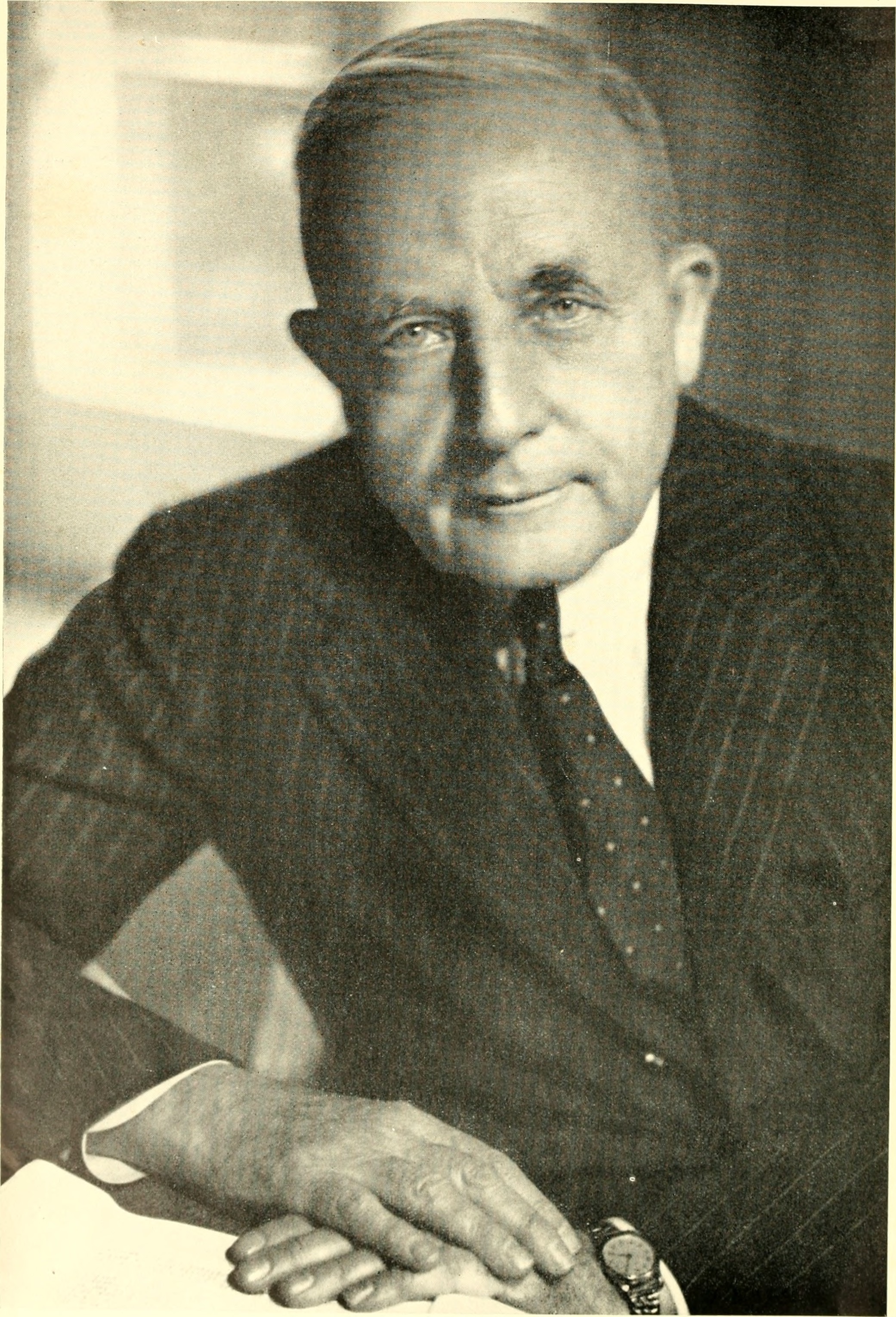

Otto Heinrich Warburg was born in Freiburg im Breisgau in 1883, close to the Swiss border. Otto's mother was the daughter of a Protestant family of bankers and civil servants from Baden. His father, Emil Warburg, had converted to Protestantism as an adult, although Emil's parents were Orthodox Jews.[4] Emil was a member of the illustrious Warburg family of Altona. Emil was also president of the Physikalische Reichsanstalt, Wirklicher Geheimer Oberregierungsrat (True Senior Privy Counselor)

Otto Warburg studied chemistry under Emil Fischer, and earned his doctorate in chemistry in Berlin in 1906. He then studied under Ludolf von Krehl and earned the degree of doctor of medicine in Heidelberg in 1911

After earning doctorates in chemistry at the University of Berlin (1906) and in medicine at Heidelberg (1911), Warburg became a prominent figure in the institutes of Berlin-Dahlem. He first became known for his work on the metabolism of various types of ova at the Marine Biological Station in Naples. His Nobel Prize in 1931 was in recognition of his research into respiratory enzymes

By 1932 Warburg had isolated the first of the so-called yellow enzymes, or flavoproteins, which participate in dehydrogenation reactions in cells, and he discovered that these enzymes act in conjunction with a nonprotein component (now called a coenzyme), flavin adenine dinucleotide. In 1935 he discovered that nicotinamide forms part of another coenzyme, now called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, which is also involved in biological dehydrogenations.

By 1932 Warburg had isolated the first of the so-called yellow enzymes, or flavoproteins, which participate in dehydrogenation reactions in cells, and he discovered that these enzymes act in conjunction with a nonprotein component (now called a coenzyme), flavin adenine dinucleotide. In 1935 he discovered that nicotinamide forms part of another coenzyme, now called nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, which is also involved in biological dehydrogenations.

While working at the Marine Biological Station, Warburg performed research on oxygen consumption in sea urchin eggs after fertilization and showed that upon fertilization the rate of respiration increases as much as sixfold. His experiments also showed that iron is essential for the development of the larval stage.

In 1918, Warburg was appointed professor at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin-Dahlem (part of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft). By 1931 he was named director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Cell Physiology, which had been founded the previous year by a donation of the Rockefeller Foundation to the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft (since renamed the Max Planck Society).

Warburg investigated the metabolism of tumors and the respiration of cells, particularly cancer cells, and in 1931 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology for his "discovery of the

While working at the Marine Biological Station, Warburg performed research on oxygen consumption in sea urchin eggs after fertilization and showed that upon fertilization the rate of respiration increases as much as six fold. His experiments also showed that iron is essential for the development of the larval stage.

In 1918, Warburg was appointed professor at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin-Dahlem (part of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft). By 1931 he was named director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Cell Physiology, which had been founded the previous year by a donation of the Rockefeller Foundation to the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft (since renamed the Max Planck Society).

Warburg investigated the metabolism of tumors and the respiration of cells, particularly cancer cells, and in 1931 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology for his "discovery of the nature and mode of action of the respiratory enzyme".[1] In particular, he discovered that animal tumors produce large quantities of lactic acid.[6] The award came after receiving 46 nominations over a period of nine years beginning in 1923, 13 of which were submitted in 1931, the year he won the prize.

In 1944, Warburg was nominated for a second Nobel Prize in Physiology by Albert SzentGyörgyi, for his work on nicotinamide, the mechanism and enzymes involved in fermentation, and the discovery of flavin (in yellow enzymes). Some sources report that he was selected to receive the award that year, but was prevented from receiving it by Adolf Hitler's regime, which had issued a decree in 1937 that forbade Germans from accepting Nobel Prizes. According to the Nobel Foundation, this rumor is not true; although he was considered a worthy candidate, he was not selected for the prize at that time.

Three scientists who worked in Warburg's lab, including Sir Hans Adolf Krebs, went on to win the Nobel Prize in future years. Among other discoveries, Krebs is credited with the identification of the citric acid cycle (or Szentgyörgyi-Krebs cycle).

Warburg's combined work in plant physiology, cell metabolism, and oncology made him an integral figure in the later development of systems biology. He worked with Dean Burk on the quantum yield of photosynthesis.

© 2022 Heinrich. All Rights Reserved. Designed by Pcube IT Services